------------

------------

------------Here is a copy of the page as it was seen at http://www.abbamail.com/news/polar_studios_closing_dn.htm

on the Internet until it was removed.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The closing of the Polar

Studios

------------ ------------

------------

-----------------

August 22, 2004

http://www.dn.se/kultur-noje/allt-ska-bort-1.300001

Everything has to go!

We're actually too late. The auction gavel was laid down hours ago and now the auction hall in Frihamnen is deserted. The furniture from the legendary ABBA studio Polar are there somewhere in the mess, some of it is nice and some of it is junk.

The Polar objects are considered junk. There was no cult factor in the marketing.

-No, those things didn't do well today, says the auctioneer who greets me.

It's August 2004. The Polar studio on Sankt Eriksgatan has been closed, due to the rent being more than doubled. The cords have been disconnected, the speakers have been torn out and a piece of Swedish social history is now scattered in the wind. Obvious objects of interest in a museum of the Swedish pop wonder are being sold off here and there.

On the Internet, ABBA's fan club have their own auction. the Polar studios' managing director was busy with one of the last recordings when the club stopped by and made bargains. You notice. There the mandolin which was used in the ABBA song "Fernando" is being sold. There the fans can make bids on Frida's signed studio stool, on pieces of the famous cloud panel and on coffee cups that may have touched Mick Jagger's lips. Or Phil Collins'. Or Jimmy Page's.

All of them have worked there.

In the business the Polar studio is talked about almost with the same historical respect as the Beatles-associated Abbey Road Studios in London. At the auctioneers' storage space none of this is noticed.

We pass a chamber pot cabinet made of mahogany and worn out leather armchairs. Finally we find the pink lounge suite, which Stikkan Anderson moved from his home to the Polar studios' reception. As recently as 1995 Rolling Stones sat in them checking videos.

The lounge suite didn't do good. It didn't get sold. The highest bid 500 kronor was one fourth of the starting price and because of that below the pain threshold. But there's still a chance. "heavily worn" it says in the auctioneers catalog.

We, the editorial staff, discuss. Cult or not?

We clinch a deal.

Benny Andersson is on an August tour. He's in the tour bus somewhere outside Hedemora when I reach him on the phone. He doesn't have anything against looking back, but emphasizes that he doesn't have anything to do with that anymore. The current owners - managing director Lennart Östlund, Marie and Tomas Ledin - took over the Polar studio in 1983, shortly after ABBA's breakup.

But just a few months ago Benny Andersson was back recording his latest album with BAO, Benny Anderssons orkester.

-We were one of the last groups, he says and I seem to trace some sentimentality in his voice.

It's a bit difficult to hear what he's saying in the background noise from the orchestra, which was a success the day before in "Allsång på Skansen". But he's telling the story from the beginning, how they had a hard time getting enough studio time "when things began working out for ABBA" in the mid-70s, how they came to the decision to build their own studio, the at the time best one possible in the world. The old cinema Riviera on Sankt Eriksgatan was purchased because of this.

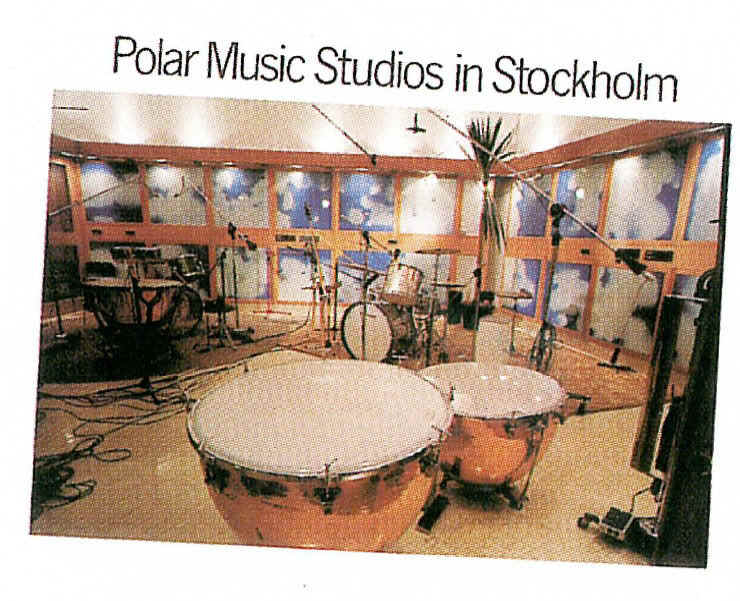

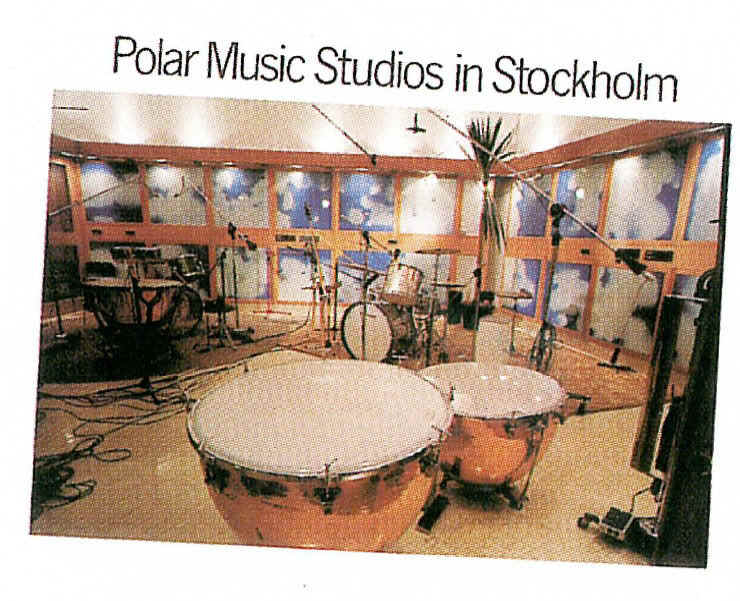

-I remember that we wanted a generously sized control room, with lots of glass around it so you could keep a good contact with each other. We wanted a hard room, a soft room and a wooden room with a bit of a resonance. Then there had to be the right equipment - a good grand piano, a hammond, some vibraphones, various percussion instruments. I think the studio looked good. A lot of space. Easy to work in. A lot of ABBA's production took place there.

The studio model was called East Lake Audio and came from the US, from the star in that area at the time, Tom Hidley. His idea, which was further developed in Stockholm, was that the recording rooms should be hanging freely, be built like boxes within a box, without any walls touching each other. A few rubber blocks were wedged under the floor and between the ceiling and the property's roof for support. You did it that way to avoid the leakage problem, soundwaves that spread when many people play.

Everything was kept together by an eight-sided control room with large glass windows.

The ABBA technician Michael Tretow says in the book "Från ABBA till Mamma Mia" (Anders Hanser and Carl Magnus Palm, 1999) how he at the most had forty-five musicians in the studio who could play at the same time, without the sound leaking between the rooms. "The cool thing about the Polar studio was that we were able to record strings at the same time as we recorded the world's loudest trumpets and trombones."

After the inauguration in May 1978, the rumor about the world's most modern studio spread. Soon international acts like Led Zeppelin and Genesis knocked on the door. ABBA recorded their three last albums "Voulez Vous", "Super trouper" and "The visitors" here. Among other things it was during the work in the Polar studio that Benny Andersson came up with the piano part which saved "The winner takes it all" for future generations.

Isn't this social history? Swedish music history? Benny Andersson sounds bothered just hearing the word. He says that he actually has tried, but had to abandon, the idea to create a syndicate to keep the studio going. But the doesn't want to be a part of saving it just for the sake of preservation.

-Museum? No, I think Vasa is better (the old preserved wooden battleship on display in Stockholm. Claes' note). Of course it's sad that the studio disappears, but music history isn't in the walls, not in the premises itself. It's possibly inside the people who happened to be there at the time.

And he can't remember a pink lounge suite. He doesn't know. Maybe it had been there. Maybe not.

The Polar studio is by Sankt Eriksbron (bridge), "behind the cold hard windows furthest back" according to the managing director Lennart Östlund's directions. I catch a glimpse of an old grill and a few bongo drums inside the door. The reception is filled with boxes and amplifiers waiting to be taken away. In the stairs there's a collection of half-antique microphone stands.

Lennart Östlund has worked here since the beginning, at first as a sound technician, now as both producer and managing director. He turns on the light in the large studio, the legendary but now empty one. In the ceiling there are empty spaces left by the speakers. The mixing table is still there, as well as the grand piano that ABBA bought - the "Thank you for the music"-grand piano, a shining Bösendorfer.

I can't resist playing a few tones on it.

We sit down in the control room and Lennart Östlund finally finds a working socket for a CD-player. Proudly I pull out the surprise out of my bag, Led Zeppelin's last album "In through the out door" in a brown paper cover. Lennart was here helping to record it in December 1978. He hasn't really listened to it since then.

-They were here for three weeks, they came on a Monday and left on a Friday. I remember that they weren't allowed to stayed at Grand (Hotel), because the drummer John Bonham had a bad reputation. But they were mellow. No one recognized them when we went out. The most important thing to them was that each week they'd have a cassette to bring home to their wives, as a proof that they had been working.

He sniffs at the fact that three songs are missing on the CD. Then once again John Bonham's powerful drums echo throughout the studio.

-He sat there, in the "stone room" in front of the cloud panel. With two sets of drums, Lennart Östlund remembers. But to get the right echo effect, we moved the speaker for the base drum out to the reception and put a microphone in front of it.

He shows me the wooden room, where the guitar player Jimmy Page stood, and the soft room, the extremely dry, where Robert Plant sang what we're listening to right now.

-Oh, he really sang false there, did you hear it? But it doesn't matter. These days you can correct things like that, but the music hasn't necessarily become any more fun because of that.

We listen to another track. The next song begins with a synthesizer sound which sounds familiar. ABBA? Lennart nods.

-Led Zeppelin liked ABBA. And that is really ABBA's synthesizer, the "Does your mother know"-synthesizer. I even think that Benny got the string sound from John Paul Jones (Led Zeppelin's bass- and piano player).

I call Benny back to check with him.

-This is how it was, says Benny. I had the same synthesizer as Led Zeppelin, a so-called dream machine. It was there in the studio. So John Paul Jones just brought his own sounds with him and put them in. He has a fantastic string sound which he had made. "Oh", I said, "that sounds so good, can I have it?"

-Then later I received a package in the mail with four cassettes in it. That string sound appears in many ABBA songs. I still use it quite often.

Such things are usually called music history. But I won't say it.

On the bulletin board outside the studio there are signed photos. "To the gang at Polar. Been great working here. Ramones." "To Polar. What a great place. Def Leppard 2001." and then a "Get to work" from Alice Cooper.

Lennart Östlund has compiled a list of groups that have worked here throughout the years. Some of the names stand out - Pretenders, Bob Hope, Rolling Stones, Backstreet Boys, Chic. And Genesis of course, the group which was the symphony rockers Lennart Östlund's favorites up until they came here to record the album "Duke" in 1979.

-I interpreted so very much in their music, I felt I knew exactly why they had done things in this or that way. Then when I worked with them, I realized that where I saw big landscapes, sunsets and seas, they just talked about eights, technique and beats. I was so disappointed.

-The best memory I have of them is that their assistant called in advance to order a ping-pong table. It was said that they were fantastic players. I hadn't played for five years, but I had barely placed myself in front of the table before I was in the lead with 21-2.

Foreign celebrities' guest appearances often meant expensive shifts that lasted forever. So eventually the Polar studio changed strategy. Swedish artists took over more and more. On Lennart's list barely any of the past 20 years biggest Swedish names are missing. More and more recording were taking place in the smaller B-studio on the floor above, when it was added on a few years later.

Lennart Östlund gets a dotted box which he puts on the table in the reception. He digs out among other things old contracts and party invitations to find the documents regarding the closing, including the exchange of opinions with culture preserving institutions.

He says that he has always known that you can't run big studios commercially for many more years. That's the way the technical development is. The rent shock only speeded up what eventually would happen anyway.

But doesn't he think that it's a big social historic mistake to just let everything go?

-What about ABBA? I wonder. Wouldn't it be natural if they step in and invest the money?

-that's the first thing that people think of. So they're supposed to build a museum about themselves? I understand if that's an unreasonable idea to them.

While he's looking for something, I admire the music machine, Rune Söderqvist's huge piece of art which is the first thing which greets a visitor. It was built on location in 1978 and it holds both drums, brass instruments, an old square piano and a chime. It can play "Thank you for the music". It still hasn't been sold.

I ask about the pink lounge suite. Lennart Östlund answers vaguely that "haven't most people sat in it", he clearly remembers Mick Jagger, but he's not really sure when it was placed there, if it was there during the ABBA years.

-Here are the papers, he says and puts forth the correspondence with the authorities.

The first letter is from 1999. The Polar studio inquires with the county administrative board's culture/environmental unit regarding the interest in preserving the studio. The county administrative board then contacts the custodian of national monuments department, which send out an employee to inspect the object. The conclusion is, somewhat surprising, that the cultural memorial law can't be applied due to the unique architectural construction.

-They explained that since the studio was built as suspended rooms it meant that it was attached to the wall. And things that aren't attached are considered furniture. Unfortunately they were prevented from culturally mark a piece of furniture.

-I replied that I could put a nail through the wall if they wanted me to, but they didn't think you could reason like that.

The next step will be the culture department. Lennart Östlund describes that process as "playing tennis against a wall of clay. No balls are returned." There's a reply from 2003, but in that letter the Polar studio is referred back to the county administrative board's culture/environmental unit. And the county administrative board haven't changed their minds when it comes the matter of furniture. In a new reply they write that the Polar studio has a high culture historic value, but that they still can't protect it.

In April of this year, when the days are numbered, Björn Ulvaeus writes a letter to the culture minister. Cautiously he writes that shouldn't they discuss the possibility to make the studio a tourist attraction. The letter leads to the matter being opened up again. In May a department employee is sent out to the studio. There's hope. But the ball gets stuck.

When I call the department in early August, I'm informed that the matter still is being prepared. Nothing can be said about the final decision.

-The day when we have formulated an opinion, it will be the Polar studios' management who'll get to hear it first, says the department's councilman Göran Blomberg in a tone of positive interest.

-But the studio isn't there anymore, I object.

-It isn't?

Benny Anderssons orkester wasn't the last one in the Polar studio. Karin Sjögren in the group Loud managed to add some vocals as late as May. A satisfied Lennart Östberg says that her music is "as close to Led Zeppelin as you can get these days".

The Polar studio isn't the only one who disappears off the map. The business is going through a dramatic structural transformation, where big studios seem to have done their part. To give a simplified picture, you can say that in the old days the musicians stood there playing and singing at the same time, even during the recording. There were lots of people who created together - producers, arrangers, technicians, musicians and artists. These days it's not unusual to have all these roles taken care of by one single person in front of a computer.

No one can afford to record in the old way anymore.

The music technician in Lennart Östlund both praises and fears the development. With the computer it's become easier to create music, more creative. New ideas are born, you can get great sounds. Some music, like modern techno, simply comes out best on a computer. He does not want to imply that things used to be better.

But along the way something is lost, something that explains why a modern compact disc, according to him, sounds more flat and boring than it should have to.

-These days I can do anything I want on the computer. I can change the pitch of the voice with autotune, I can move the singing, I can stretch it lengthwise. But back then we only had the best singers, the best musicians, the best studio. Today you can make anyone sound good. It becomes like an academic template, so boring to listen to.

He has his own list of music's unnecessary victims on the altar of technology. It goes from beginning to end and begins with songwriting. Today's computer composers write using "click", as Lennart Östlund calls it, they get a rhythm/beat on the computer and then add their own music to it. The songwriter who at first sat down by the piano let the music get it's natural tempo. He could vary it, maybe let the tempo slow down and then make it faster in the chorus. Or completely change it. Surprise.

-There was a certain attraction to it. Few go through that trouble these days. Everything becomes streamlined. But I would like to say that music is communication and emotions. It's not about measuring technology.

Next unnecessary limitation is about the sound level. Lennart Östlund talks about a race, which is propelled by both record companies and radio stations. The stronger, the better it's regarded. And no one wants to sound worse than the competitor.

When the computer now gives the possibility to take shortcuts with the music, flatten it to raise the general impression, everyone graciously accepts it. Away with the most silent silence which grows into the strongest strong. Full blast the whole time, so that the song can be heard from the beginning to the end on a noisy motorway. So that no one changes the station and the STIM money (money that the composers get paid each time the song is played on the radio. Claes' note).

-Sometimes I feel ashamed when I hear my own recent productions. The experience, the dynamic are gone. It's like a flat foil wall of equally thick music where it's complete democracy from the smallest cymbal to the singing. Nothing happens when the singer sings with a stronger voice and there's not less going on when he's singing more relaxed. You almost don't get any shivers up your spine with new music anymore, says Lennart Östlund.

On my way out I try on Agnetha's and Frida's headphones, the ones you see in the photos in the ABBA book. They are forgotten in the reception. They managed avoiding the auction.

I look through the book and find more of Anders Hanser's fantastic photos from the Polar studio's days of glory. It seems as if the ABBA members play and sing at the same time, even during the recordings.

Lennart Östlund talked about getting back "the shivers up your spine" into the music. He talked about a particular presence which appears when many people play together at the same time, about the expression of the performance and the imprint on the music. Of course it's difficult for a single person in front of a computer to capture that.

Suddenly I realize why the Polar studio's old furniture has such a great symbolic value, even culture historic.

The future's music production probably won't need any pink lounge suites.

By Ingrid Carlberg

-----------------

Thanks to ABBAMAILer Claes Davidsson, Orlando, Florida, USA